I’d guess that if you told the average person that Great White Shark size was declining, they probably wouldn’t be too upset. But in reality, this trend is incredibly dangerous for their populations and the ocean ecosystem as a whole. Though it seems like a simple concept, the idea of size is much more than just a number. Instead, it is a strong influence upon most every aspect of the organism, helping to determine how to adapt to fit its particular niche. In the case of Great White Sharks, its size is essential to its status as an apex predator of the oceans.

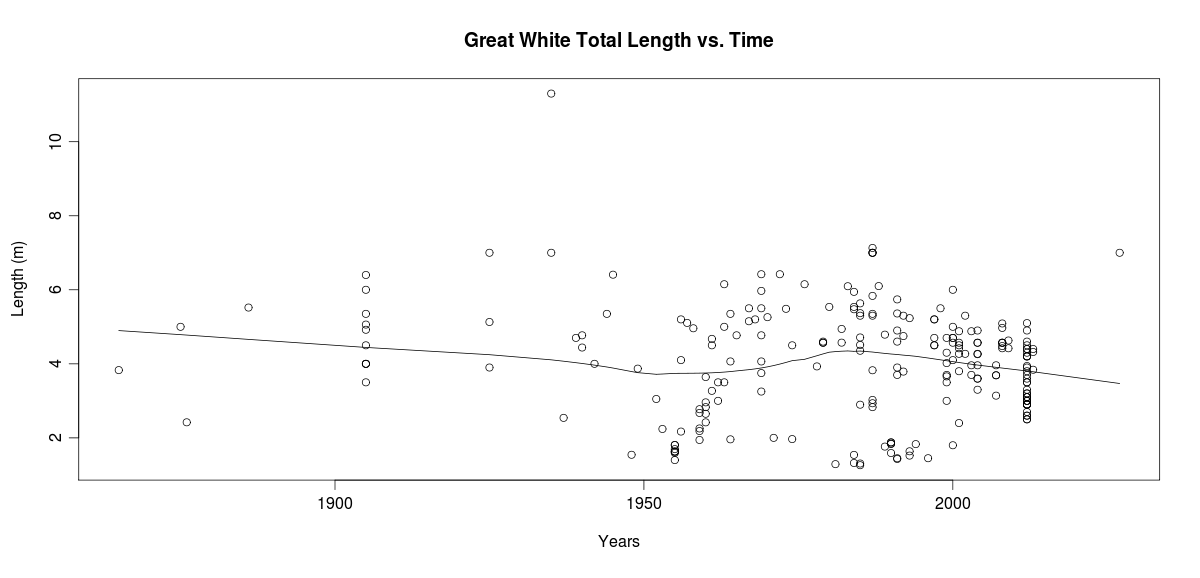

There is an subtle but noticeable decline in size. Over the last few decades, this decrease seems to be a relatively steady and gradual. Is it artifact? It could result from just sampling bias and this will obviously require more analysis.

This pattern if real is cause for concern.Due to their reproductive biology, size is an indication of a problem greater than just dimension changes.

Though a slightly lower size wouldn’t be a big deal on a functional level for an individual Great White Shark, on a population level, the decline in size indicates a shift in the percentage of sharks that are of reproductive age. Therefore, as the average size decreases, so do the number of sharks that can pup each year. As a species, these organisms are vulnerable as a result of their slow growth and whopping 15-year wait until maturity.

This graph also seems to indicate a slight increase in size from about 1960-1980. Though there’s not a complete explanation as to why this happened, it’s possible that the decrease in fishing during World War II may have given populations some time to recover, or perhaps this is just an effect of there being fewer sizing reports that this time. This isn’t the first time that an oddity around this time frame has been reported, since Cliff et al. 1998 also noted a decrease in catch in South African waters between 1973-1993. Perhaps this decreased catch helped their populations replenish over this period, but it’s hard to know for sure.

In the end, it seems that Great White Sharks are now facing their greatest pressure in 16 million years – humans. After surviving this long in the delicately balanced ocean ecosystem, the decision is now in our hands as to whether to push these sharks into extinction, or create a system to protect these crucial apex predators and allow their populations to recover. Declining Great White Shark sizes should be an indication that we need to reverse our thinking. Rather than protecting ourselves from sharks, we need to protect sharks from humans.

Resources:

Bruce, Barry D. “Preliminary observations on the biology of the white shark, Carcharodon carcharias, in south Australian waters.” Marine and Freshwater Research 43.1 (1992): 1-11.

Fergusson, I., Compagno, L.; Marks, M. (2000).“Carcharodon carcharias in IUCN 2012″. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, Vers. 2009.1. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

Gilmore, R. Grant. “Reproductive biology of lamnoid sharks.” Environmental Biology of Fishes 38.1-3 (1993): 95-114.

Distribution and autoecology of the great white shark in the NE Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea, Chapter 30 in “Great White Sharks: Ecology and Behaviour”, (1998), (AP Klimley & DG Ainley, Eds.), Academic Press.